Abstract

Objectives. We assessed how the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) reporting guideline was used by authors and journal editors in journals’ instructions to authors. We also evaluated its impact on reporting completeness and study quality.

Methods. We extracted data from publications that cited TREND on how TREND was used in those reports; we also extracted information on journals’ instructions to authors. We then undertook a case–control study of relevant publications to evaluate the impact of using TREND.

Results. Between 2004 and 2013, TREND was cited 412 times, but it was only evidently applied to study reports 47 times. TREND was specifically mentioned 14 times in the sample of 61 instructions to authors. Some evidence suggested that use of TREND was associated with more comprehensive reporting and higher study quality ratings.

Conclusions. TREND appeared to be underutilized by authors and journal editors despite its potential application and benefits. We found evidence that suggested that using TREND could contribute to more transparent and complete study reports. Even when authors reported using TREND, reporting completeness was still suboptimal.

It is now widely acknowledged that public health policymakers need to include evidence from both nonrandomized and randomized study designs.1–6 There is evidence, however, that the quality of reporting in public health intervention studies is variable1 and that outcome reporting bias exists.7 In addition, poor and incomplete reporting of research adversely affects evidence synthesis and represents a major waste of scarce resources (e.g., time and research funds) and harms that could otherwise be avoided.8 One strategy to address these concerns has been the development, publication, and promotion of reporting guidelines. Reporting guidelines are checklists, flow diagrams, or detailed texts to guide authors in reporting specific types of research that are developed using clear and transparent methods.9 Reporting guidelines aim to ensure that fewer studies are missing information that is critical for understanding the methods and results. Simply, if key details of study methods or context are not reported, the findings of studies cannot be used by others.10 More complete reporting should also increase the likelihood that studies will be appropriately included within evidence syntheses.

Ten years ago, the American Journal of Public Health published the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) statement.11 The HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis team of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in conjunction with editors and representatives of 18 HIV/AIDS–focused journals developed TREND over the course of a 2-day meeting. TREND differs from other reporting guidelines because it focuses on evaluations of public health and behavioral interventions with nonrandomized designs. TREND also includes items pertinent to assessing the effectiveness of interventions and external validity. TREND has 5 sections that address the title and abstract, introduction, method, results, and discussion sections of journal articles; it is available at http://www.cdc.gov/trendstatement.

The authors of the TREND statement did not define what they referred to as “public health,” “behavioral,” or “nonrandomized” interventions. However, they did state that TREND was to be used for

... intervention evaluation studies using nonrandomized designs, not for all research using nonrandomized designs. Intervention studies would necessarily include 1) a defined intervention that is being studied and 2) a research design that provides for an assessment of the efficacy or effectiveness of the intervention.11(p362)

Not defining key terminology has the potential benefit of being widely inclusive, but may also risk being perceived as unclear.

Following the publication of TREND, several publications expressed a mix of support for it and suggestions for how it could be improved.1,12 To date, there have been no revisions, extensions, or evaluations of TREND. This is in contrast to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting of Trials (CONSORT)13 reporting guideline on which TREND was largely based. CONSORT focuses on aspects of study design and methodology relevant to internal validity in randomized controlled trials. It has been revised twice13,14 and evaluated widely15 in the time since TREND was first published. In addition, extensions to CONSORT for specific types of trials (e.g., pragmatic trials16), interventions (e.g., for nonpharmacological interventions17), and fields (e.g., social and psychological interventions18,19) have been developed. Findings from these evaluations have indicated that the use of CONSORT is associated with the improved reporting of randomized controlled trials.20–22

TREND has the potential to play a significant role in improving the evidence base of public health interventions, and could do so if used in conjunction with the new template for intervention description and replication checklist.23 However, there is an outstanding need to establish whether TREND is of use and benefit. This is fundamental for either further promotion or revision of TREND or refinement of dissemination strategies. Our main objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of TREND and to address 3 research questions: (1) How is TREND used by authors of research articles? (2) How is TREND used in journals’ “instructions to authors”? (3) What is the impact of using TREND on the reporting completeness of articles?

A fourth question addressing the issue of what factors affect authors’ and editors’ use of reporting guidelines was addressed in a second study (a currently unpublished article). Because of the exploratory nature of research questions 1 and 2, no hypotheses have been made. Regarding the third question, it was hypothesized that studies that reported the use of TREND would have higher levels of reporting completeness than those that could have used TREND, but did not report doing so.

METHODS

A detailed overview of the methods used to conduct our study is freely available in a previously published protocol.24

We conducted the study in 2 parts. The first, addressed research questions 1 and 2. The second, which used a case–control design, compared reporting completeness in samples of articles that did and did not report the use of TREND (question 3).

We defined the use of TREND as being a citation of or “reference within a published article to TREND being referred to inform or guide the planning, conduct and/or reporting of the research study and results.”24(p4)

TREND Use by Authors of Research Articles

We identified, retrieved, and coded studies that cited the original TREND statement to examine how authors used TREND. We used both the Web of Science and Scopus databases “cited by” search functions to identify articles that cited TREND. We searched both databases because it was previously established that individual databases do not include all citations.25,26

Adding Google Scholar to the repertoire of search engines could have yielded additional results, but Google Scholar was inefficient and less specific than the Web of Science and Scopus,27 and it is likely that many irrelevant records would have had to be searched for little, if any, gain. We identified studies that used TREND to inform reporting within this sample through a manual search, and we extracted relevant details (e.g., study design).

TREND Use in Journals’ Instructions to Authors

We searched for references to the TREND guidelines in the instructions to authors information in journals that published articles that used TREND to inform reporting or were listed as TREND supporters on the CDC Web site (March 2013). Key words and phrases were copied verbatim when references were made to reporting guidelines (e.g., “authors should use TREND when reporting studies with nonrandomized designs”). In the event that 2 or more journals referred to the same instructions to authors, they were treated independently.28 We also recorded if a journal’s instructions to authors had a requirement for completed checklists to be submitted with manuscripts or if it had links to the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) and TREND websites.

We used a 1-way analysis of variance to check whether there were differences in journal status (as indicated by a proxy: impact factor) among journals that published articles that used TREND and those listed as supporters of the reporting guideline. (Note: impact factors are the ratio of the overall frequency with which articles are cited to the number of research articles, technical notes, and reviews [i.e., “citable” articles as defined by Institute for Scientific Information] within a journal from the preceding 2-year period.29 Impact factors are not as objective as they might be seen as and used, because the method of calculating them is susceptible to biases [e.g., coverage and language preference of the Science Citation Index]29; furthermore they are not an indication of study or article quality. Despite these issues, impact factors are known to influence authors’ and editors’ practices regarding manuscript submission and publication.)

TREND and the Reporting Completeness of Articles

We assessed the impact of TREND by comparing 2 samples of study reports—1 that used TREND and 1 that could have used TREND, but did not report doing so. We selected comparator studies by first identifying a pool of studies that could have used TREND, but did not report doing so, by using a focused search strategy (included as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org) within MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and EMBASE. We then screened the search results (with 25% being randomly selected and double-screened by either J. P. or M. P.). Finally, we randomly selected an equal number of comparator articles (not citing TREND) to those that reported the use of TREND.24 We calculated reporting completeness as the percentage of items identified in a published article that were listed in the TREND checklist or another quality appraisal tool.

There are multiple components (e.g., “clearly defined primary and secondary outcome measures”) within some items on the TREND checklist, and no instructions are given on how authors should comply with these components, that is, whether they need to report both the primary and secondary outcomes before they are judged as having have reported the item. Because an evaluation of TREND has not been undertaken previously, and the use of it is usually recommended rather than mandatory, we adopted a generous criterion when assessing reporting completeness. This meant that if 1 part of the item was reported (e.g., primary, but not secondary outcome, measures were reported), we coded it as reported.

We assessed the respective samples of articles for reporting completeness using the TREND checklist (the primary outcome measure), the Effective Public Health Practice Project-Quality Assessment tool (EPHPP-QA),30 and the revised Graphical Appraisal Tool for Epidemiological studies (GATE).31 Reviewers were not blinded to which article sample a study was in (i.e., use or nonuse of TREND) because of limited resources. Also, article details, such as journal title and year of publication, were not concealed from reviewers because there was no strong evidence to indicate that this affected assessment of reporting completeness and study quality.21

T. F. assessed all the articles included in the study. A second reviewer assessed a random selection of 25% of both samples, and the interrater reliability between reviewers was checked. Results revealed good interrater reliability for reporting completeness with the TREND checklist (Cronbach α = 0.86), moderate reliability for the EPHPP-QA (Cronbach’ α = 0.49), and poor reliability for GATE (Cronbach α = 0.34). Because of the low level of interrater reliability with GATE, it was excluded from subsequent analyses.

To examine whether reporting completeness (as measured by the TREND checklist) was related to use of TREND, we conducted an analysis of covariance test by controlling for the year of publication and the impact factor. Because there were 2 outliers within the impact factor, the main analyses were run twice, once with and once without them, to gauge their effect. We used SPSS version 21 (IBM, Armonk, NY)32 to conduct all analyses.

We also conducted analyses to explore whether the stated use of TREND was associated with better reporting of particular aspects of studies, such as the theory used to inform interventions, discussion of fidelity of intervention, steps taken to minimize bias, blinding, and discussion of generalizability.

RESULTS

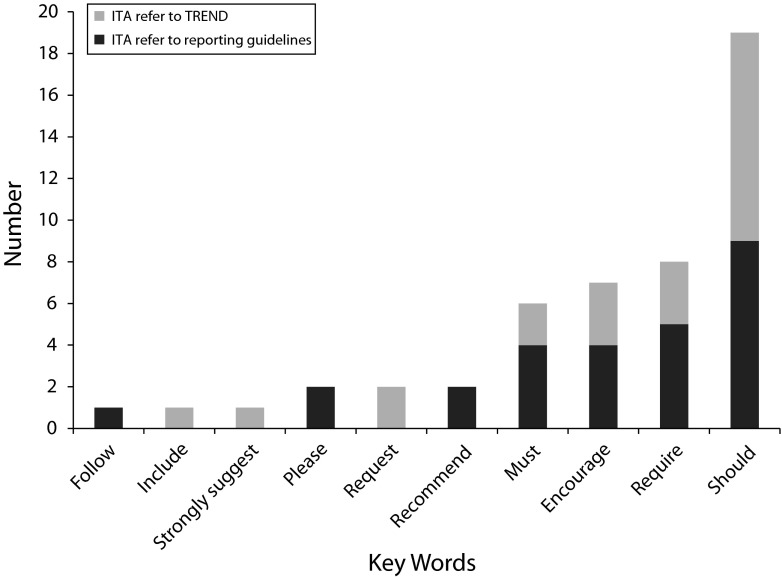

Between the time that TREND was published in 2004 and 2013, TREND was cited in 412 publications. Figure 1 shows the numbers and types of articles that TREND was cited in and how they were used. TREND was most often cited in articles without apparently being applied in any direct way.

FIGURE 1—

Citations of Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) by use and type of article: 2004–2013.

Note. RG = reporting guideline. Some articles and editorials used TREND in multiple ways.

Nineteen percent (77 of 412) of articles that cited TREND were primary research. Of these, 61% reported that they used TREND to inform the reporting of the research (47 of 77), with more than half of them indicating that they used it for guiding their whole article.

Secondary research articles (i.e., narrative and systematic literature reviews, with or without meta-analyses) were the most frequent to cite TREND (38%; 157 of 412). Although most of these only cited TREND (e.g., “We encourage authors to follow… the TREND statement when reporting on their intervention evaluation”33(p140)), when it was used, it was almost always used as a quality assessment tool. Of the editorials (13% of the sample) that cited TREND, more than half did so in the context of endorsing or promoting its use by authors when submitting to the journal.

Overall, these results showed that authors used TREND for a variety of purposes, used it relatively infrequently, and used it often in ways other than its intent.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of primary studies that used TREND, demonstrating the variability among these articles. The impact factor of the journals (at the year of publication, if available) that published the articles ranged from 0 to 38, with a median of 2.16 (SD = 5.76).

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Primary Research Studies That Used Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND): 2004–2013

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

| Web of Science classification of subject of studya | |

| Medicine | 21 (34) |

| Psychology | 10 (16) |

| Public health | 9 (15) |

| Nutrition/dietetics | 4 (7) |

| Nursing | 3 (5) |

| Other (including health care services, criminology, law, sports science, social work, substance abuse) | 9 (15) |

| None | 5 (8) |

| Study design | |

| Nonrandomized controlled trial | 32 (68) |

| Pre–post test without control group | 14 (30) |

| Cross section | 1 (2) |

| Locations of evaluations | |

| North America | 23 (49) |

| Europe | 11 (23) |

| Australasia | 5 (11) |

| Africa | 4 (9) |

| South East Asia | 2 (4) |

| South America | 1 (2) |

| Multinational | 1 (2) |

| Intervention targets | |

| People living with a health condition | 24 (51) |

| People at risk for developing a health condition | 18 (38) |

| Health professionals | 5 (11) |

| Interventions | |

| Treatment as usual | 17 (23) |

| Multifactorial | 9 (12) |

| Behavioral | 7 (9) |

| No intervention | 7 (9) |

| Psychological | 6 (8) |

| Education | 4 (5) |

| Computer or Internet based | 3 (4) |

| Wait-list control | 3 (4) |

| Medicine | 2 (3) |

| Other (e.g., financial support, medical simulator for staff training) | 17 (23) |

| Intervention delivery | |

| Group-based | 15 (32) |

| Specific subgroups within the population | 12 (26) |

| One-to-one | 9 (19) |

| General population | 6 (13) |

| Both group and one-to-one sessions | 3 (6) |

| Not reported | 2 (4) |

| Sources of funding | |

| Government/public funding | 35 (49) |

| Nongovernment organizations | 15 (32) |

| Private charitable sources | 9 (13) |

| Private industry | 6 (8) |

| Not reported | 6 (8) |

Some articles were given more than one category/discipline by Web of Science.

TREND use in Journals’ Instructions to Authors

Journal characteristics.

To add context to authors’ use of TREND, it was important to examine how journals promoted the requirements of reporting guidelines. Sixty-one journals’ instructions to authors were searched for references to TREND. More than half of these journals (57%) published the articles we found that had used TREND, with the remainder claimed as supporters of TREND (43%) according to the CDC. (For additional details, see data available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org.)

Journals’ use of reporting guidelines in instructions to authors.

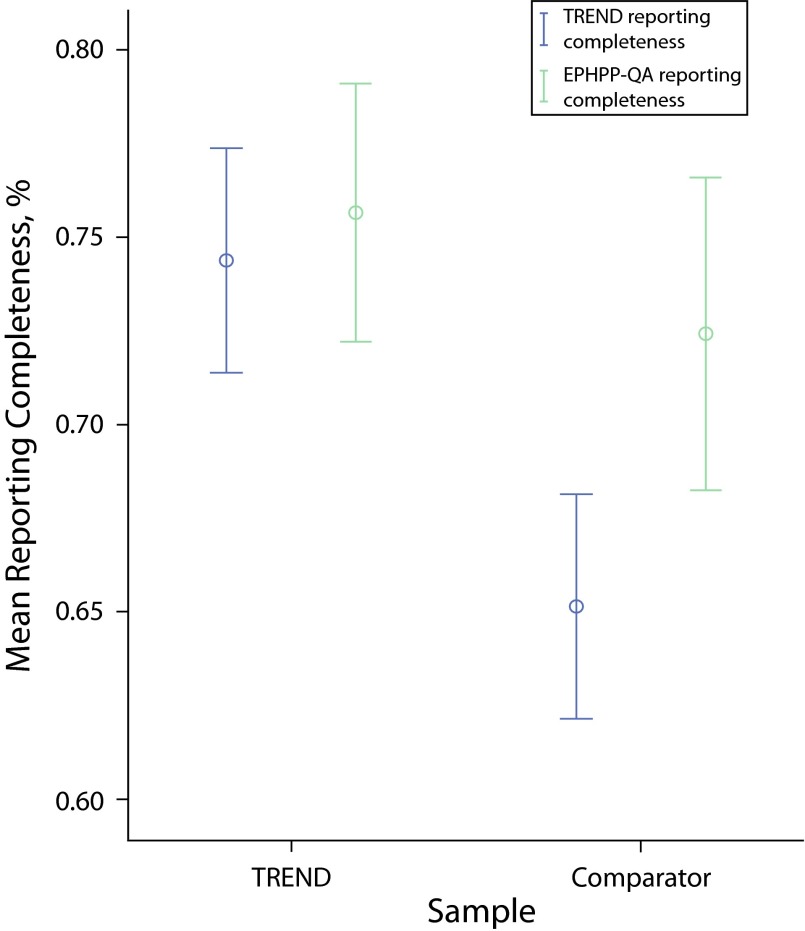

Overall, use or promotion of TREND and other reporting guidelines by journals was variable. Fewer than half (29 of 61) of the journals included in our sample referred to a set of reporting guidelines in their instructions to authors. The most frequently mentioned reporting guidelines in this sample were CONSORT (28 of 61), Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; 18 of 61), and TREND (14 of 61).

Within the instructions to authors that referred to reporting guidelines, most (17 of 29) used language such as “should,” “encourage,” or “request.” However, 12 journals used unambiguous language to convey to authors that it was mandatory to use reporting guidelines in the preparation of their articles. These journals used “must,” “require,” or statements such as: “The criteria for publication include the application of the CONSORT, TREND and PRISMA statements.” Figure 2 shows the frequency of key words used by journals in their instructions to authors.

FIGURE 2—

Key words used in instructions to authors (ITA) regarding reporting guideline use: 2004–2013.

Twenty-three percent of the instructions to authors (14 of 61) referred to TREND, and of those that did, 4 (28%) used unambiguous language in relation to requiring (or otherwise) that authors use it. Nearly all of the instructions that referred to TREND (12 of 14) provided a link to the CDC Web site or reporting guideline. Less than half (10 of 26) of the journals identified as supporters of TREND actually referred to it in their instructions to authors.

In summary, and similar to authors’ use of TREND, it appears that TREND is being used inconsistently and infrequently by academic journals.

TREND and the Reporting Completeness of Articles

Reporting completeness and use of TREND.

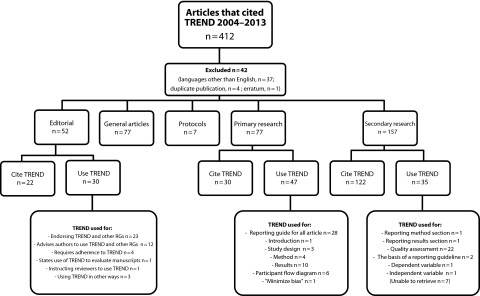

Figure 3 shows that studies that used the TREND checklist had a statistically significant greater reporting completeness than those that did not, when assessed using the TREND checklist. However, when using the EPHPP-QA as a measure of reporting completeness, the comparison was nonsignificant but also showed that articles that used TREND had a slightly greater reporting completeness. (Details of the reporting completeness per TREND item are available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org.)

FIGURE 3—

Mean reporting completeness by Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) usage and completeness measure: 2004–2013.

Note. EPHPP-QA = Effective Public Health Practice Project-Quality Assessment. Whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals.

With the outliers included, the analysis of covariance also indicated that use of TREND was significantly associated with greater reporting completeness after controlling for the effects of year of publication and journal impact factor (F[1, 90] = 17.67; P < .001). That is, authors who indicated using TREND to inform the reporting of their study were more likely to include more relevant information about its conduct and findings after controlling for the effects of changes in publication standards over time and the impact factor than authors who did not use TREND. The findings did not change when the observed outliers were excluded.

Results from our analyses that examined the impact of TREND on specific items, rather than overall reporting completeness, revealed varied results. For example, differences existed between the samples for the reporting of theories used to inform the intervention design, but not for the steps taken to minimize bias. (Further details are available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org.)

Use of TREND and study quality.

A significant association between the study quality rating and the use of TREND (χ2[2, n = 94] = 11.72; P = .003) suggested that studies that used TREND tended to be of higher quality, as judged by the EPHPP. (Further details are available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org.)

DISCUSSION

Improving the reporting of evaluations of public health interventions is of fundamental importance to assessing the validity and generalizability of individual studies, enabling more comprehensive evidence synthesis and ultimately, better decision-making. We aimed to contribute to this by describing how, and how much, the TREND statement was used by authors and editors, and to test the hypothesis that authors reporting the use of TREND would have higher levels of reporting completeness than those authors who did not.

Underutilization of TREND by Authors

We found evidence indicating that authors of primary research studies used TREND infrequently. This was both as a percentage of the number of times it was cited and compared with other reporting guidelines (e.g., CONSORT).34 However, when authors of primary research articles used it, they used it as intended by TREND’s developers. This was in contrast with secondary researchers who used TREND as a study quality assessment tool, although it was not designed for this purpose.

Only 1 other study, to our knowledge, specifically examined how authors used reporting guidelines. In that instance, Da Costa et al. found that the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement was frequently misused as a quality assessment tool in systematic reviews.35 Together with our results, this suggests that there is a need for developing specific study quality or risk of bias tools for nonrandomized study designs. Higgins et al. recently reached a similar conclusion in their article, which was based on a workshop organized by the Non-Randomized Studies Methods Group of the Cochrane Collaboration.36

Variation and Ambiguity in the Promotion of TREND

Keeping in mind that instructions to authors are documents that change over time,37 what we found reflected a “snapshot” of a sample of journals taken in 2013. Journal editors in journals’ instructions to authors used TREND relatively infrequently. Other studies that examined the frequency with which specific reporting guidelines were cited in instructions to authors found that, for example, CONSORT was referred to between 3%38 and 53%39 of the time.28,40,41 Although we found that TREND was referred to in approximately 25% of the journals’ instructions to authors, this percentage was probably artificially inflated because the journals included claimed that they were TREND supporters or were journals that had published articles that used TREND.

Editorial endorsement of the use of a reporting guideline varies and ranges between weak (i.e., where a preference or suggestion for the use of the guideline is made) to strong (i.e., where the submission of a completed checklist with a manuscript is required and enforced by editorial staff). Although “should” is an indication of a strong preference for the use of reporting guidelines, it is still just that. The strength of editorial endorsement likely affects authors’ likelihood of using reporting guidelines,42 but further empirical research is required. Our finding that there was a large degree of heterogeneity and ambiguity in the choice of words used by editors in instructions to authors when referring to the requirement to use reporting guidelines was consistent with other results.38,40,41,43 The ambiguity and relative weakness in instructions to authors might partially explain why the use of TREND was so low.

Taken together, the first 2 key findings suggested that there were failures in the dissemination and implementation strategy of the TREND guideline. Data from our study did not enable us to do anything more than speculate on the factors that affected the uptake and use of TREND. We recently conducted a second study using survey and interviews with editors and authors to explore this issue in depth (unpublished article).

Evidence That TREND Improves Reporting Completeness

Using 2 different measures of reporting completeness, we found that studies in which TREND was used to inform reporting were more likely to have greater reporting completeness than studies that did not use TREND. However, even when TREND was used to report studies, reporting completeness scores were only at 75%, indicating that there is considerable room for improvement and that use of TREND itself does not wholly achieve its intended purpose. In addition, the result informed us that differences exist in perceptions of what “reporting” constitutes between reviewers assessing reporting completeness and authors using reporting guidelines.

Making comparisons with other studies was problematic because of a lack of evaluations of reporting guidelines,42,44 different methods used in evaluating impact, and sometimes an absence of detail regarding reporting completeness data.45 Nevertheless, from the data that were available, our results showed reporting completeness to be within the range of that reported by other studies.46,47 However, our estimates of reporting completeness were likely to be inflated because of the generous, rather than conservative, coding scheme we adopted when coding whether a particular item was reported.

Use of TREND Is Associated With Better Study Quality

The finding that use of TREND, when using EPHPP-QA, was associated with higher study quality (distinct from the impact factor) was unlikely to be solely because of better reported studies having more information. This was because the scoring of the EPHPP-QA does not always calculate nonreporting as a weakness of the study design. Thus, although the association between use of TREND and higher ratings of study quality appeared encouraging, it was not a causal link. Replication is required before stronger claims can be made.

Study Limitations

Three main limitations affected the strength of findings in our study. First, the main outcome measure of reporting completeness—the TREND checklist—was also the intervention of interest. To address this, we used a second measure of reporting completeness, the EPHPP-QA. It was chosen in the absence of other purposefully designed measures of reporting completeness and because of its relevance to nonrandomized study designs. Although it showed a similar direction in results, the differences were not statistically significant. It thus provided evidence that contrasts with that obtained when using the TREND checklist as the measure of reporting completeness. A second limitation of our study was that assessments of reporting completeness and study quality were not blinded. Despite having a second reviewer assess a random sample of 25% of articles, we could not completely discount the possibility that reviewer biases accounted for any differences in reporting completeness and study quality rating. Lastly, it was possible that the pool of studies randomly selected to be comparators were not representative of the population of articles that could have used the TREND guideline, but did not. A different sample could have yielded different reporting completeness results.

Conclusions and Implications

Without an ongoing dissemination and implementation strategy, TREND’s uptake and use has remained relatively low. Lack of widespread adoption of better reporting practices in public health risks potentially valid and relevant evidence being excluded from systematic reviews.

Replication of this study is required and could be done using purpose-made measures that assess reporting completeness or with blinded assessors. Similarly, further investigation is warranted regarding the association between study quality and use of TREND, possibly through examination of whether studies that use TREND are more likely to be included in systematic reviews.

If TREND is to have a role in the future, we expect that potential users would need to be convinced of the benefits of its use, and recommend that a new promotion and dissemination strategy be developed. Uptake of TREND could be increased if more journals required and enforced the use of TREND to report studies with nonrandomized designs. In addition, an updated TREND guideline could increase its perceived relevance. For example, simplifying certain items could improve ease of use and provide the focus for renewed promotion to opinion leaders and professional societies. As with other reporting guidelines, uptake could also be increased by improving the accessibility and usability of the TREND checklist (e.g., see the CONSORT checklist48). We also suggest that there is potential for combining efforts with other initiatives to improve the quality of description of public health interventions. For example, the behavior change taxonomy of Michie et al. could form part of the foundation of a common language to be used within the framework provided by TREND.49 Combining such initiatives with the continued support of the American Journal of Public Health for TREND and other reporting guidelines would have benefits for researchers and the community alike.

Acknowledgments

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) for the South West Peninsula.

Note. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health in England.

Human Participant Protection

Because there were no human participants, this study was exempt from ethics approval by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Exeter Medical School, United Kingdom.

References

- 1.Armstrong R, Waters E, Moore L et al. Improving the reporting of public health intervention research: advancing TREND and CONSORT. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008;30(1):103–109. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waters E, Priest N, Armstrong R et al. The role of a prospective public health intervention study register in building public health evidence: proposal for content and use. J Public Health (Oxf) 2007;29(3):322–327. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly MP, Stewart E, Morgan A et al. A conceptual framework for public health: NICE’s emerging approach. Public Health. 2009;123(1):e14–e20. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medical Research Council. Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions. London: Medical Research Council; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith RD, Petticrew M. Public health evaluation in the twenty-first century: time to see the wood as well as the trees. J Public Health (Oxf) 2010;32(1):2–7. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Victora CG, Habicht J-P, Bryce J. Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):400–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearson M, Peters J. Outcome reporting bias in evaluations of public health interventions: evidence of impact and the potential role of a study register. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(4):286–289. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.122465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet. 2014;383(9913):267–276. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62228-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Weeks L, Ocampo M et al. Describing reporting guidelines for health research: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):718–742. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson NW, Howes FS, Gupta S, Doyle JL, Waters E. Interventions implemented through sporting organisations for increasing participation in sport. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004812.pub2. CD004812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):361–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Klesges LM, Glasgow RE. TREND: an important step, but not enough. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(9):1474. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340 doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.72352. c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285(15):1987–1991. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CONSORT Group. Impact of and adherence to CONSORT Statement. CONSORT Group Web site. Available at: http://www.consort-statement.org/about-consort/impact-of-consort. Accessed August 14, 2014.

- 16.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008;337 doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2390. a2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant SP, Mayo-Wilson E, Melendez-Torres GJ, Montgomery P. Reporting quality of social and psychological intervention trials: a systematic review of reporting guidelines and trial publications. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065442. e65442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery P, Grant S, Hopewell S et al. Protocol for CONSORT-SPI: an extension for social and psychological interventions. Implement Sci. 2013;8:99. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plint AC, Moher D, Morrison A et al. Does the CONSORT checklist improve the quality of reports of randomised controlled trials? A systematic review. Med J Aust. 2006;185(5):263–267. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prady SL, Richmond SJ, Morton VM, MacPherson H. A systematic evaluation of the impact of STRICTA and CONSORT recommendations on quality of reporting for acupuncture trials. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001577. e1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner L, Moher D, Shamseer L et al. The influence of CONSORT on the quality of reporting of randomised controlled trials: an updated review. Trials. 2011;12(suppl 1) A47. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuller T, Pearson M, Peters JL, Anderson R. Evaluating the impact and use of Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Non-randomised Designs (TREND) reporting guidelines. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002073. e002073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulkarni AV, Aziz B, Shams I, Busse JW. Comparisons of citations in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar for articles published in general medical journals. JAMA. 2009;302(10):1092–1096. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Burnham JF, Lemley T, Britton RM. Citation analysis: comparison of Web of Science®, Scopus™, SciFinder®, and Google Scholar. J Electron Resour Med Libr. 2010;7(3):196–217. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giustini D, Boulos MNK. Google Scholar is not enough to be used alone for systematic reviews. Online J Public Health Inform. 2013;5(2):214. doi: 10.5210/ojphi.v5i2.4623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunath F, Grobe HR, Rucker G et al. Do journals publishing in the field of urology endorse reporting guidelines? A survey of author instructions. Urol Int. 2012;88(1):54–59. doi: 10.1159/000332742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong P, Loh M, Mondry A. The “impact factor” revisited. Biomed Digit Libr. 2005;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1742-5581-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.NICE. Methods for Development of NICE Public Health Guidance. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N et al. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):133–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larson EL, Cortazal M. Publication guidelines need widespread adoption. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(3):239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.da Costa BR, Cevallos M, Altman DG, Rutjes AWS, Egger M. Uses and misuses of the STROBE statement: bibliographic study. BMJ Open. 2011;1(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000048. e000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins JPT, Ramsay C, Reeves BC et al. Issues relating to study design and risk of bias when including non-randomized studies in systematic reviews on the effects of interventions. Res Synth Methods. 2013;4(1):12–25. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wager E, Fiack S, Graf C, Robinson A, Rowlands I. Science journal editors’ views on publication ethics: results of an international survey. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(6):348–353. doi: 10.1136/jme.2008.028324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X-Q, Tao K-m, Zhou Q-h et al. Endorsement of the CONSORT statement by high-impact medical journals in China: a survey of instructions for authors and published papers. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030683. e30683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mills E, Wu P, Gagnier J, Heels-Ansdell D, Montori VM. An analysis of general medical and specialist journals that endorse CONSORT found that reporting was not enforced consistently. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(7):662–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altman DG. Endorsement of the CONSORT statement by high impact medical journals: survey of instructions for authors. BMJ. 2005;330(7499):1056–1057. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7499.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hopewell S, Altman D, Moher D, Schulz K. Endorsement of the CONSORT statement by high impact factor medical journals: a survey of journal editors and journal ‘instructions to authors’. Trials. 2008;9(1):20–26. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevens A, Shamseer L, Weinstein E, Yazdi F, Turner L, Thielman J et al. Relation of completeness of reporting of health research to journals’ endorsement of reporting guidelines: systematic review. BMJ. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3804. g3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shamseer L. Lessons Learned From the Development of a Strategy to Improve the Uptake of CONSORT. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simera I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Hoey J. Guidelines for reporting health research: the EQUATOR network’s survey of guideline authors. PLoS Med. 2008;5(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050139. e139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Delaney M, Meyer E, Cserti-Gazdewich C et al. A systematic assessment of the quality of reporting for platelet transfusion studies. Transfusion. 2010;50(10):2135–2144. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bastuji-Garin S, Sbidian E, Gaudy-Marqueste C et al. Impact of STROBE statement publication on quality of observational study reporting: interrupted time series versus before-after analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064733. e64733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parsons NR, Hiskens R, Price CL, Achten J, Costa ML. A systematic survey of the quality of research reporting in general orthopaedic journals. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(9):1154–1159. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B9.27193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.CONSORT Group. CONSORT Downloads. CONSORT Website. Available at: http://www.consort-statement.org/consort-2010. Accessed August 14, 2014.

- 49.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]