Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Historical shifts are occurring in marijuana policy. The effect of legalizing marijuana for recreational use on rates of adolescent marijuana use is a topic of considerable debate.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the association between the legalization of recreational marijuana use in Washington and Colorado in 2012 and the subsequent perceived harmfulness and use of marijuana by adolescents.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

We used data of 253 902 students in eighth, 10th, and 12th grades from 2010 to 2015 from Monitoring the Future, a national, annual, cross-sectional survey of students in secondary schools in the contiguous United States. Difference-indifference estimates compared changes in perceived harmfulness of marijuana use and in past-month marijuana use in Washington and Colorado prior to recreational marijuana legalization (2010–2012) with post legalization (2013–2015) vs the contemporaneous trends in other states that did not legalize recreational marijuana use in this period.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Perceived harmfulness of marijuana use (great or moderate risk to health from smoking marijuana occasionally) and marijuana use (past 30 days).

RESULTS

Of the 253 902 participants, 120 590 of 245 065(49.2%) were male, and the mean (SD) age was 15.6 (1.7) years. In Washington, perceived harmfulness declined 14.2%and 16.1% among eighth and 10th graders, respectively, while marijuana use increased 2.0% and 4.1% from 2010–2012 to 2013–2015. In contrast, among states that did not legalize recreational marijuana use, perceived harmfulness decreased by 4.9% and 7.2%among eighth and 10th graders, respectively, and marijuana use decreased by 1.3%and 0.9%over the same period. Difference-in-difference estimates comparing Washington vs states that did not legalize recreational drug use indicated that these differences were significant for perceived harmfulness (eighth graders:%[SD], −9.3 [3.5]; P = .01; 10th graders:%[SD], −9.0 [3.8]; P = .02) and marijuana use (eighth graders:%[SD], 5.0 [1.9]; P = .03; 10th graders:%[SD], 3.2 [1.5]; P = .007). No significant differences were found in perceived harmfulness or marijuana use among 12th graders in Washington or for any of the 3 grades in Colorado.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Among eighth and 10th graders in Washington, perceived harmfulness of marijuana use decreased and marijuana use increased following legalization of recreational marijuana use. In contrast, Colorado did not exhibit any differential change in perceived harmfulness or past-month adolescent marijuana use following legalization. A cautious interpretation of the findings suggests investment in evidence-based adolescent substance use prevention programs in any additional states that may legalize recreational marijuana use.

Historical shifts are occurring in attitudes toward marijuana and in state marijuana policy in the United States. The proportion of adolescents who perceive great risk of harm in using marijuana once or twice a week has decreased from 55% in 2007 to 44% in 2012,1 and 58% of adults now support legalization of recreational marijuana.2 Since 1996, 28 states and Washington, DC, have passed legislation permitting the use of marijuana for medical purposes.3 In 2012, Colorado and Washington became the first 2 states to legalize the recreational use of marijuana for adults. Alaska, Oregon, and Washington, DC, followed suit in 2014, and California, Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada approved the legalization of recreational adult use in the November 2016 ballots.4 The potential effect of legalization for recreational use on rates of marijuana use in the United States is a topic of considerable debate.5–9

While legalization for recreational purposes is currently limited to adults, potential effects on adolescent marijuana use are of particular concern. Some adolescents who try marijuana will go on to long-term use, with an accompanying range of adverse outcomes.10–16 However, the effect of legalizing marijuana for adult recreational use on adolescents is unknown. Studies of the association between medical marijuana legislation (MML) and adolescent marijuana use indicate that while states that passed MML have higher rates of adolescent marijuana use, rates were already higher in these states before passage of the laws and that rates did not increase after the laws were passed.17–19 However, studies of MML cannot be generalized to laws on recreational use, which may have much broader effects17 through such factors as pricing,6 advertising, availability, and/or implicit messages to teens that marijuana use is acceptable or nonrisky.20,21 Therefore, understanding the effect of legalization for recreational purposes on adolescent marijuana use is of critical importance.

In this study, we examine the association between legalization of recreational marijuana use for adults (ie, persons 18 years or older) in Washington and Colorado and the change in perceived harmfulness of marijuana use and in self-reported adolescent marijuana use before and after legalization. Both states passed laws legalizing recreational marijuana use on November 6, 2012. At the time of enactment, possession for personal use was legalized in both states, and cultivation for personal use was also legalized in Colorado. Stores that sold marijuana opened in 2014 (in January in Colorado and July in Washington), and the first grower licenses in Washington were issued in March 2014.

We tested whether adolescents in Washington and Colorado were less likely to perceive marijuana as harmful and more likely to use marijuana in the 3 years following legalization (2013–2015) compared with the 3 years prior to legalization (2010–2012) and compared these findings with trends in states that did not legalize recreational marijuana use. While full implementation of the law did not occur until 2014, enactment of the law could in itself have an effect on marijuana use by increasing advertising of the product, changing perceptions of the harmfulness of marijuana, and legalizing possession.

Key Points.

Question

How did the prevalence of adolescent marijuana use change in Washington and Colorado following legalization of recreational marijuana use?

Findings

In this difference-in-difference analysis of 253 902 adolescents in 47 states, marijuana use among eighth and 10th graders in Washington increased 2.0% and 4.1%, respectively, between 2010–2012 and 2013–2015; these trends were significantly different from trends in states that did not legalize marijuana. In Colorado, the prevalence of marijuana use prelegalization and postlegalization did not differ.

Meaning

A cautious interpretation of the findings suggests investment in adolescent substance use prevention programs in additional states that may legalize recreational marijuana use.

Methods

Setting, Participants, Procedures

The Monitoring the Future (MTF) study annually conducts national cross-sectional surveys of eighth, 10th, and 12th graders.22,23 Data are collected in approximately 400 schools in the spring in the contiguous United States via self administered questionnaires. We analyzed data collected from 2010 to 2015, approximately 3 years before and 3 years after legalization of recreational marijuana use in Colorado and Washington. The comparison group included 45 states that had not legalized recreational marijuana use in this period. Oregon and Washington, DC, were excluded from our analysis because they legalized recreational marijuana use in 2014; Alaska was already excluded from the MTF study, as it is not a contiguous state.

The study uses a multistage random sampling design. Stages include US geographic area, schools within regions of the country (with probability proportionate to school size), and students within schools. Up to 350 students per grade per school are included, with random selection of classrooms within schools. Schools participate for 2 consecutive years. Nonparticipating schools are replaced with others closely matched on geographic location, size, and urban city. Student response for the MTF study is 81%to 91%for all years and grades, with almost all nonresponse due to absenteeism and less than 1%refusals. Of all selection sample units, 92% to99 % obtained 1 or more participating schools in all study years; the lack of a time trend in school participation rates24 suggests that school nonresponse does not affect results. Across the 6 years (2010–2015), 253 902 students provided data on marijuana use (89 316 eighth graders, 85 110 tenth graders, and 79 476 twelfth graders). In Colorado, 2982 students in 17 schools (28 school surveys, because some schools were surveyed in more than 1 year) provided data on marijuana use between 2010 and 2015, and in Washington, 5509 students in 30 schools (47 school surveys) provided data.

Consistency in measures and data collection procedures was strictly maintained across years and grade levels. Students completed questionnaires in classrooms unless larger group administrations were required. The MTF study representatives distributed and collected questionnaires using standardized procedures, including instructions to teachers to avoid proximity to students to maintain confidentiality.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Michigan and Columbia University. Letters were sent in advance to parents to inform them about the study and to explain that participation was voluntary and responses were anonymous (for eighth and 10th graders) or confidential (for 12th graders). The letters also provided parents with a means to decline their child’s participation if necessary.

Measures

Outcomes

The primary outcome was an individual-level binary variable: any marijuana use within the prior 30 days.17,25 We also conducted a sensitivity analysis using a measure of marijuana use frequency (ie, no use, 1–2 occasions, or 3 or more occasions in the past 30 days). Self-administered forms and data collection procedures are designed to maximize validity of substance use reporting. Validity of MTF substance reports is supported by low question nonresponse, high proportions consistently reporting illicit drug use, and strong construct validity.23

Perceived harmfulness of marijuana use was the second outcome of interest. Respondents were asked, “How much do you think people risk harming themselves (physically or in other ways), if they smoke marijuana occasionally?” Response options included “norisk,” “slight risk,” “moderate risk,” “great risk,” and “can’t say, drug unfamiliar.” We compared those who perceived “no risk” or “slight risk” with those who perceived “great risk” or “moderate risk” (“can’t say” was considered missing).

Main Exposure

The primary exposure was the state-level recreational marijuana laws (RML). The variable was used to compare changes in perceived harmfulness and marijuana use in adolescents living in states that passed RML(Colorado and Washington each separately)with contemporaneous changes in the other 45 contiguous states that had not passed RML. Because RML was enacted in Colorado and Washington in November 2012, 2010 to 2012were considered pre-RML, while 2013 to 2015were considered post-RML years. Sensitivity analyses compared changes in Colorado and Washington with the 20 other contiguous states (besides Colorado and Washington and excluding Oregon) that ever passed MML.

School-Level and State-Level Covariates

School-level control variables included the number of students per grade within the school (1–99, 100–199, 200–299, 300–399, 400–499, 500–699, and 700 or more), public vs private school, and urban/suburban (ie, schools located within a Metropolitan Statistical Area26) vs rural. State-level control variables included the proportion of the population in each state that was male, white, age 10 to 24 years, and 25 years or older without a high school education. Census values from 2010 were used for years of the study period.

Individual Covariates

Individual covariates included self-reported age, sex, race/ethnicity(self-defined as white, black, Hispanic, Asian, multiple, or other), and socioeconomic status, defined by highest parental education (high school not completed, high school graduate/equivalent, some college, 4-year college degree, or higher).

Statistical Analysis

Difference-in-difference estimates and associated tests were conducted by comparing the change in past-month marijuana use and in perceived harmfulness of marijuana use from 3 years prior to RML (2010–2012) with the 3 years after RML (2013–2015) in Washington and Colorado (included as separate categories in the same model) vs contemporaneous changes in the 45 contiguous states that did not pass RML. Adjusted prevalence estimates of marijuana use and of perceived harmfulness of use, 95% CIs, and tests of difference indifference contrasts were obtained from logistic regression models, including a dichotomous time indicator (2010–2012 vs 2013–2015), a 3-category RML exposure indicator (Colorado vs Washington vs non-RML as separate categories), the interaction of time and the 3-category RML exposure indicator, and all individual-, school-, and state-level covariates. Logistic regression models were estimated using generalized estimating equations controlling for clustering of individuals within schools with robust standard error estimation. The predicted marginal approach was used to test risk differences between pre-RML and post-RML within Colorado and within Washington and then to test difference-in-difference between these differences in Colorado and in Washington vs contemporaneous differences in other non-RML states.27

SUDAAN version 11.0(RTI International)with PREDMARG and PRED_EFF commands within RLOGIT was used for all analyses, and the exact code is provided in the eAppendix in the Supplement. Because sampling was conducted separately by grade, regression models were fit stratified by grade to provide grade-specific effects of RML.

Three sensitivity analyses were also conducted. First, we examined frequency (ie, number of occasions) of marijuana use in the past 30 days instead of any use vs none. Second, we repeated regressions for marijuana use, limiting other states to only include those that passed MML. Finally, we used a test of trend in the 12 years prior to RML to validate the parallel path assumption28 for difference-in-difference estimators, ie, that trends were not already differentially increasing in Colorado and Washington prior to passage of the law.

Results

Table 1 presents characteristics of the study respondents, the schools they attended, and the states they resided in during the pre-RML and post-RML periods examined.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Monitoring the Future Study Respondents From 2010 to 2015

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Colorado | Washington | Non-RML or MMLa | MML Onlyb | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| 2010–2012 | 2013–2015 | 2010–2012 | 2013–2015 | 2010–2012 | 2013–2015 | 2010–2012 | 2013–2015 | |

| Sample size, No. | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Schools surveyed | 14 | 14 | 24 | 23 | 575 | 549 | 449 | 434 |

|

| ||||||||

| Students | 1320 | 1662 | 2912 | 2597 | 71 313 | 65 421 | 57 729 | 50 948 |

|

| ||||||||

| Individual characteristics | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Marijuana use | 262 (19.9) | 287 (17.3) | 407 (13.9) | 376 (14.5) | 10 349 (14.5) | 9012 (13.8) | 9895 (17.1) | 8056 (15.8) |

|

| ||||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 15.7 (1.9) | 14.9 (1.6) | 15.5 (1.8) | 15.1 (1.7) | 15.6 (1.7) | 15.6 (1.7) | 15.6 (1.7) | 15.6 (1.7) |

|

| ||||||||

| Male | 631 (49.5) | 810 (50.9) | 1453 (51.4) | 1206 (48.4) | 34 158 (49.5) | 30 857 (49.1) | 27 408 (48.9) | 24 067 (49.1) |

|

| ||||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Black | 51 (3.9) | 123 (7.6) | 101 (3.5) | 101 (4.0) | 10 607 (15.2) | 10 355 (16.2) | 4091 (7.3) | 4105 (8.3) |

|

| ||||||||

| White | 737 (57.1) | 337 (20.8) | 1916 (67.2) | 1383 (55.1) | 42 822 (61.2) | 35 574 (55.7) | 29 845 (53.1) | 24 752 (50.1) |

|

| ||||||||

| Hispanic | 294 (22.8) | 875 (54.1) | 331 (11.6) | 427 (17.0) | 7757 (11.1) | 8775 (13.7) | 11 468 (20.4) | 11 177 (22.6) |

|

| ||||||||

| Asian | 55 (4.3) | 39 (2.4) | 176 (6.2) | 188 (7.5) | 1728 (2.5) | 1858 (2.9) | 3940 (7.0) | 2939 (5.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| Multiple | 124 (9.6) | 214 (13.2) | 236 (8.3) | 314 (12.5) | 5806 (8.3) | 6313 (9.9) | 5397 (9.6) | 5392 (10.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| Other | 29 (2.3) | 29 (1.8) | 91 (3.2) | 96 (3.8) | 1238 (1.8) | 1039 (1.6) | 1485 (2.6) | 1064 (2.2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Parental socioeconomic status | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| <High school | 114 (9.2) | 481 (32.8) | 242 (8.9) | 309 (13.3) | 5286 (8.0) | 5197 (8.7) | 5059 (9.5) | 4768 (10.3) |

|

| ||||||||

| High school | 210 (17.0) | 346 (23.6) | 461 (16.9) | 472 (20.3) | 14 115 (21.4) | 12 088 (20.2) | 9771 (18.4) | 8372 (18.1) |

|

| ||||||||

| Some college | 286 (23.1) | 317 (21.6) | 722 (26.5) | 543 (23.3) | 18 238 (27.6) | 15 711 (26.3) | 13 345 (25.1) | 11 441 (24.7) |

|

| ||||||||

| College | 626 (50.7) | 322 (22.0) | 1299 (47.7) | 1006 (43.2) | 28 457 (43.1) | 26 844 (44.9) | 25 033 (47.1) | 21 777 (47.0) |

|

| ||||||||

| School characteristics | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Public schools | 1255 (95.1) | 1662 (100) | 2864 (98.4) | 2444 (94.1) | 65 968 (92.5) | 60 739 (92.8) | 49 556 (85.8) | 44 853 (88.0) |

|

| ||||||||

| Urban schools | 1278 (96.8) | 1579 (95.0) | 2271 (78.0) | 1897 (73.1) | 52 901 (74.2) | 48 044 (73.4) | 50 399 (87.3) | 45 097 (88.5) |

|

| ||||||||

| State characteristics, mean (SD) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Male | 50.1 (0.0) | 50.1 (0.0) | 49.8 (0.0) | 49.8 (0.0) | 49.1 (0.4) | 49.1 (0.4) | 49.1 (0.6) | 49.1 (0.6) |

|

| ||||||||

| White | 69.9 (0.0) | 69.9 (0.0) | 72.5 (0.0) | 72.5 (0.0) | 69.0 (13.5) | 67.6 (13.7) | 58.2 (15.3) | 59.0 (15.9) |

Abbreviations: MML, medical marijuana laws; RML, recreational marijuana laws.

States that had not enacted RML or MML.

States that had enacted MML but not RML.

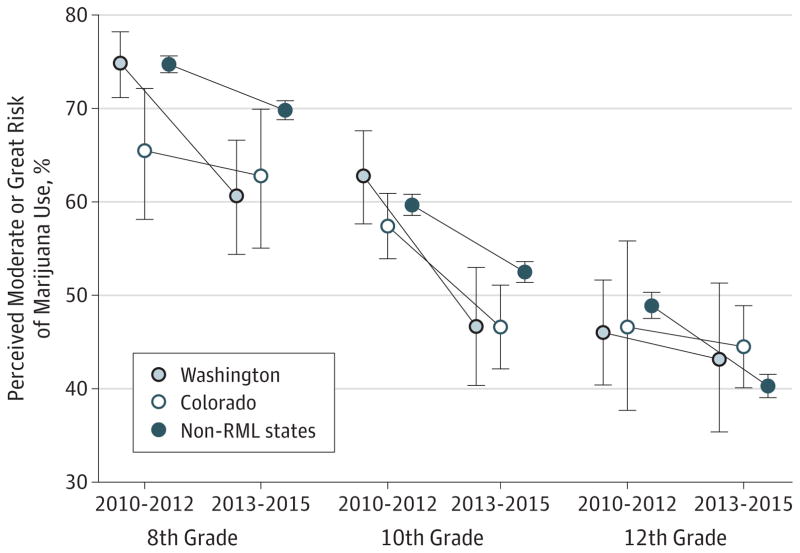

Table 2 and Figure 1 present the adjusted prevalence of perceived harmfulness of marijuana use in 2010 to 2012 and 2013 to 2015 in Colorado, Washington, and non-RML states by grade. In Washington, perceived harmfulness declined by 14.2%and 16.1% among eighth and 10th graders, respectively, in this period. In contrast, among states that did not legalize recreational marijuana use, perceived harmfulness decreased by 4.9% and 7.2% among eighth and 10th graders, respectively, over the same period. These differences in trends between Washington and non-RML states were significant (eighth graders:%[ SD], −9.3 [3.5]; P = .01; 10th graders:%[SD], −9.0[3.8]; P = .02). No difference was found among 12th graders in Washington or among students in any grade in Colorado compared with non-RML states.

Table 2.

Difference-in-Difference Tests of Past-Month Prevalence of Perceived Great or Moderate Risk of Marijuana Use Before and After RML by Grade

| State | Risk, % (95% CI) | Difference Before vs After RML, % (SE) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before RML (2010–2012) | After RML (2013–2015) | |||

| 8th Grade | ||||

| Colorado | 65.5 (58.1 to 72.1) | 62.8 (55.1 to 69.9) | −2.7 (5.0) | .59 |

| Washington | 74.9 (71.2 to 78.2) | 60.7 (54.4 to 66.6) | −14.2 (3.4) | <.001 |

| Non-RML | 74.7 (73.8 to 75.6) | 69.8 (68.8 to 70.8) | −4.9 (0.6) | <.001 |

| Difference-in-difference Colorado vs non-RML | NA | NA | 2.2 (5.0) | .65 |

| Difference-in-difference Washington vs non-RML | NA | NA | −9.3 (3.5) | .01 |

| 10th Grade | ||||

| Colorado | 57.5 (53.9 to 60.9) | 46.6 (42.2 to 51.1) | −10.9 (2.0) | <.001 |

| Washington | 62.8 (57.6 to 67.6) | 46.6 (40.4 to 53.0) | −16.1 (3.7) | <.001 |

| Non-RML | 59.7 (58.6 to 60.8) | 52.5 (51.4 to 53.6) | −7.2 (0.8) | <.001 |

| Difference-in-difference Colorado vs non-RML | NA | NA | −3.7 (2.2) | .09 |

| Difference-in-difference Washington vs non-RML | NA | NA | −9.0 (3.8) | .02 |

| 12th Grade | ||||

| Colorado | 46.7 (37.7 to 55.8) | 44.5 (40.2 to 48.9) | −2.2 (4.8) | .65 |

| Washington | 46.0 (40.4 to 51.6) | 43.2 (35.4 to 51.3) | −2.8 (4.7) | .55 |

| Non-RML | 48.9 (47.5 to 50.3) | 40.3 (39.1 to 41.5) | −8.6 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Difference-in-difference Colorado vs non-RML | NA | NA | 6.4 (4.9) | .19 |

| Difference-in-difference Washington vs non-RML | NA | NA | 5.8 (4.8) | .22 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; RML, recreational marijuana laws.

Figure 1. Perceived Harmfulness of Marijuana Use Before and After Legalization in Colorado, Washington, and States Without Recreational Marijuana Laws (RML).

The solid lines indicate the adjusted prevalence of perceived harmfulness of marijuana use before and after RML in Colorado, Washington, and non-RML states by grade. Error bars indicate 95%CIs.

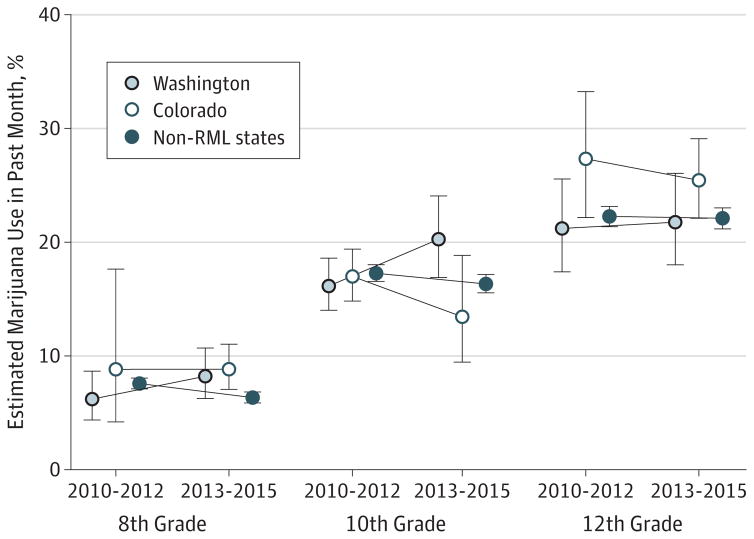

Table 3 and Figure 2 present the adjusted prevalence of past month marijuana use in 2010 to 2012 and 2013 to 2015 in Colorado, Washington, and non-RML states. In Washington, marijuana use among eight hand 10th graders increased by 2.0% and 4.1%, respectively, during this time. In contrast, marijuana use prevalence among eight hand 10 th graders in states with no RML decreased by 1.3% and 0.9%, respectively, over the same period. While the increase in marijuana use among eighth graders in Washington was not significantly greater than zero, the significant decrease in use among eighth graders in non-RML states suggests that if there had been no legalization in Washington, then marijuana use among eighth graders in this state would decrease rather than remain stable, as it did. Difference indifference tests indicated that these differences between Washington and non-RML state trends were significant (eighth graders:%[SD], 5.0[1.9]; P = .03; 10th graders:%[SD], 3.2 [1.5]; P = .007). The change in marijuana use was concentrated among nonusers (whose prevalence decreased) and regular (ie, 3 or more times in the past 30 days) users (whose prevalence increased) (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Table 3.

Difference-in-Difference Tests of Past-Month Prevalence of Marijuana Use Before and After RML by Grade

| State | Used Marijuana in Past Month, % (95% CI) | Difference Before vs After, % (SE) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before RML (2010–2012) | After RML (2013–2015) | |||

| 8th grade | ||||

| Colorado | 8.9 (4.2 to 17.6) | 8.9 (7.1 to 11.0) | −0.01 (3.3) | >.99 |

| Washington | 6.2 (4.4 to 8.7) | 8.2 (6.3 to 10.7) | 2.0 (1.4) | .16 |

| Non-RML | 7.6 (7.1 to 8.1) | 6.3 (5.9 to 6.8) | −1.3 (0.3) | <.001 |

| Difference-in-difference Colorado vs non-RML | NA | NA | 1.3 (3.3) | .72 |

| Difference-in-difference Washington vs non-RML | NA | NA | 3.2 (1.5) | .03 |

| 10th grade | ||||

| Colorado | 17.0 (14.8 to 19.4) | 13.5 (9.5 to 18.8) | −3.5 (2.4) | .14 |

| Washington | 16.2 (14.0 to 18.6) | 20.3 (16.9 to 24.1) | 4.1 (1.8) | .02 |

| Non-RML | 17.3 (16.5 to 18.0) | 16.4 (15.6 to 17.2) | −0.9 (0.5) | .07 |

| Difference-in-difference Colorado vs non-RML | NA | NA | −2.6 (2.4) | .30 |

| Difference-in-difference Washington vs non-RML | NA | NA | 5.0 (1.9) | .01 |

| 12th grade | ||||

| Colorado | 27.4 (22.2 to 33.3) | 25.5 (22.1 to 29.1) | −1.9 (2.9) | .52 |

| Washington | 21.2 (17.4 to 25.6) | 21.8 (18.0 to 26.1) | 0.6 (2.7) | .83 |

| Non-RML | 22.3 (21.4 to 23.2) | 22.1 (21.2 to 23.0) | −0.2 (0.6) | .79 |

| Difference-in-difference Colorado vs non-RML | NA | NA | −1.7 (3.0) | .57 |

| Difference-in-difference Washington vs non-RML | NA | NA | 0.8 (2.8) | .79 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; RML, recreational marijuana laws.

Figure 2. Marijuana Use Before and After Legalization in Colorado, Washington, and States Without Recreational Marijuana Laws (RML).

The solid lines indicate the adjusted prevalence of past-month marijuana use before and after RML in Colorado, Washington, and non-RML states by grade. Error bars indicate 95%CIs.

No difference was found in the prevalence of marijuana use among 12th graders in Washington or in Colorado in any grade. Results were nearly identical when the reference states were recoded as the other 20 MML states (eTable 2 in the Supplement). No significant increasing trend in marijuana use was found from 2001 to 2012 in Colorado or Washington compared with other states (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

We assessed whether the perceived harmfulness of marijuana use and prevalence of marijuana use changed in adolescents in Colorado and Washington after legalization of adult recreational marijuana use in 2012 in comparison with other states that did not pass such legislation. Within Washington, the rate of perceived harmfulness of marijuana use decreased and the rate of past-month use increased among eighth and 10th graders following passage of RML, while there was no significant change among 12th graders. Specifically, the prevalence of regular users of marijuana increased and the prevalence of nonusers decreased; no change was observed among occasional users. In contrast, Colorado did not exhibit any change in perceived harmfulness or past-month adolescent marijuana use following RML enactment. These findings remained when the comparison states were limited to the 20 states that have passed MML, indicating that the effects we found are specific to legislation permitting recreational use.

To our knowledge, this is the first national empirical test of a change in adolescent perceived harmfulness of marijuana and marijuana use associated with RML enactment. The only other study that addressed these issues compared marijuana use among 2 different cohorts of eighth graders in Tacoma, Washington: one surveyed before RML and the other immediately following RML.29 That study found higher marijuana use in the second cohort, although the difference was not significant.29 The lack of a comparison group limited inference about whether these findings were related to RML.

The post-RML increase in adolescent marijuana use in Washington could have several explanations. First, our findings suggest that legalization of recreational marijuana use in 2012 reduced stigma and perceptions of risk associated with marijuana use.20,21 A shift in social norms regarding marijuana use may have, in turn, increased marijuana use among adolescents in Washington. Second, legalization may have increased availability, increasing adolescent access to marijuana indirectly through third-party purchases. Third, legalization could have decreased the price of marijuana in the black market,6,30 particularly after the first grower licenses in Washington were issued in March 2014 and the first stores opened in July 2014. The latter 2 mechanisms are less likely explanations for the change in marijuana use observed in this study, as grower licenses and stores did not start until 2014 and our study ended in 2015. Fourth, the increase in marijuana use observed in Washington could be due to other changes occurring at the same time as RML rather than to RML itself. For example, each school participates in the MTF for only 2 consecutive years, suggesting that changes in marijuana use might be partly because of school variation over the years. However, we controlled for school characteristics and census based state-level demographic characteristics, and our use of pre-post difference-in-difference tests provides the basis for appropriate conclusions about changes in marijuana use, assuming that trends in non-RML states reflect what would have happened in Colorado and Washington if they had not passed RML. Future studies should examine the effects of specific implementation procedures and other possible mechanisms as explanations for the observed increase in Washington after additional post-RML years in Washington accumulate.31

The post-RML change in perceived harmfulness and marijuana use in Washington was focused among eighth and 10th graders. The lack of change in perceived harmfulness among 12th graders suggests that one potential explanation for the lack of change in marijuana use observed among 12th graders is that they already had formed attitudes and beliefs related to marijuana use prior to the enactment of RML. Hence, their marijuana use was less likely to change following RML. The reasons behind an age-specific effect of RML on perceived harmfulness and marijuana use should be further investigated in future research.

We found no comparable change in perceived harmfulness or marijuana use in Colorado. This difference may be related to the different degree of commercialization of marijuana prior to legalization in Washington and Colorado. Colorado had a very developed medical marijuana dispensary system prior to legalization, with substantial advertising, to which youth were already exposed.32 Washington, on the other hand, did not provide legal protection to medical marijuana stores. Therefore, the degree of commercialization and advertising of these collectives was substantially lower than in Colorado. In addition, rates of perceived harmfulness in Colorado were already lower and rates of marijuana use were already higher than rates in Washington and non-RML states prior to legalization. Preexisting low levels of perceived harmfulness and high levels of use may have constrained further short term increases following RML enactment. The longer-term effect of RML implementation on adolescent marijuana use in Colorado is still to be determined. Further, approximately half as many schools were included in the Colorado sample (17 schools) compared with the Washington sample (30 schools), which may have limited power to detect an effect in Colorado, particularly if the schools were located far away from marijuana dispensaries.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, marijuana use was self reported, leading to potential response bias associated with the legalization of marijuana. However, the data collection method has been validated in previous methodological studies, and the assessment was conducted in confidential settings. Second, MTF selects schools within regions of the country (with probability proportional to school size) rather than within states. In the present study, students in 17 schools (28 school surveys) in Colorado and 30 schools (47 school surveys) in Washington provided data across the 6 years. A greater number of schools would have been advantageous, and the sample design may lead to discrepancies between MTF results and those found in other large-scale surveillance efforts. Third, the study does not include adolescents who were absent from school or who have dropped out of school; these adolescents likely represent a higher-risk subset of adolescents.23 Inferences are thus restricted to school-attending adolescents, who comprise the large majority of the US adolescent population. Fourth, analyses are specific to the states of Washington and Colorado and cannot be generalized to the rest of the United States. Fifth, this study focused on marijuana; future studies should examine the effect of RML on other types of substance use.

Conclusions

Our study showed a significant decrease in the perceived harm associated with marijuana use and an increase in past-month marijuana use following enactment of RML among students in eighth and tenth grades in Washington but not in Colorado. Although further data will be needed to definitively address the question of whether legalizing marijuana use for recreational purposes among adults influences adolescent use, and although these influences may differ across different legalization models, a cautious interpretation of the findings suggests investment in evidence-based adolescent substance use prevention programs33–38 in any additional states that may legalize recreational marijuana use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The design, conduct, data collection, and management of the Monitoring The Future study was sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the US National Institutes of Health and carried out by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan, funded by grant R01DA001411. The analysis, interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript was funded by grant R01DA034244 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Additional support is acknowledged from grants K01DA030449 and R01DA040924 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Dr Cerdá), grant K01AA021511 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Dr Keyes), and the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Drs Hasin and Wall).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

Author Contributions: Dr Wall and Ms Feng had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Cerdá, Wall, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Pacula, Galea, Hasin.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Cerdá, Wall, Feng, Keyes, Sarvet, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Pacula.

Drafting of the manuscript: Cerdá, Wall.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Wall, Feng, Keyes, Sarvet, Pacula.

Obtained funding: Schulenberg, O’Malley, Hasin.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Schulenberg, Pacula, Galea.

Study supervision: Cerdá, Schulenberg, Galea, Hasin.

References

- 1.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results From the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Accessed April 1, 2016]. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresults2012/NSDUHresults2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones JM Gallup. [Accessed April 19, 2016];US, 58%back legal marijuana use. http://www.gallup.com/poll/186260/back-legal-marijuana.aspx.

- 3.NORML. [Accessed November 29, 2016];Medical marijuana. http://norml.org/legal/medical-marijuana-2.

- 4.NORML. [Accessed August 25, 2016];Election 2016: marijuana ballot results. http://norml.org/election-2016.

- 5.Hall W, Lynskey M. The challenges in developing a rational cannabis policy. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22(3):258–262. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283298f36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall W, Weier M. Assessing the public health impacts of legalizing recreational cannabis use in the USA. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97(6):607–615. doi: 10.1002/cpt.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Room R. Legalizing a market for cannabis for pleasure: Colorado, Washington, Uruguay and beyond. Addiction. 2014;109(3):345–351. doi: 10.1111/add.12355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US News. [Accessed November 20, 2015];Should marijuana use be legalized? http://www.usnews.com/debate-club/should-marijuana-use-be-legalized.

- 9.The Editorial Board. [Accessed July 27, 2014];The New York Times calls for marijuana legalization. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/07/27/opinion/sunday/high-time-marijuana-legalization.html.

- 10.Brook JS, Lee JY, Finch SJ, Seltzer N, Brook DW. Adult work commitment, financial stability, and social environment as related to trajectories of marijuana use beginning in adolescence. Subst Abus. 2013;34(3):298–305. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2013.775092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(40):E2657–E2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renard J, Krebs MO, Jay TM, Le Pen G. Long-term cognitive impairments induced by chronic cannabinoid exposure during adolescence in rats: a strain comparison. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;225(4):781–790. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2865-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arseneault L, Cannon M, Poulton R, Murray R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult psychosis: longitudinal prospective study. BMJ. 2002;325(7374):1212–1213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lev-Ran S, Roerecke M, Le Foll B, George TP, McKenzie K, Rehm J. The association between cannabis use and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2014;44(4):797–810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maggs JL, Staff J, Kloska DD, Patrick ME, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg J. Predicting young adult degree attainment by late adolescent marijuana use. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(2):205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasin DS, Wall M, Keyes KM, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the USA from 1991 to 2014: results from annual, repeated cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(7):601–608. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wall MM, Poh E, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin DS. Adolescent marijuana use from 2002 to 2008: higher in states with medical marijuana laws, cause still unclear. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(9):714–716. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harper S, Strumpf EC, Kaufman JS. Do medical marijuana laws increase marijuana use? replication study and extension. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khatapoush S, Hallfors D. “Sending the wrong message”: did medical marijuana legalization in California change attitudes about and use of marijuana? J Drug Issues. 2004;34:751–770. doi: 10.1177/002204260403400402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason WA, Hanson K, Fleming CB, Ringle JL, Haggerty KP. Washington State recreational marijuana legalization: parent and adolescent perceptions, knowledge, and discussions in a sample of low-income families. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(5):541–545. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.952447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. The Monitoring the Future Project After Four Decades: Design and Procedures: Paper No. 82. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research at The University of Michigan; 2015. [Accessed May 30, 2016]. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/occpapers/mtf-occ82.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use: 1975–2015. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research at The University of Michigan; 2016. [Accessed May 30, 2016]. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2010. I. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research at The University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keyes KM, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, et al. The social norms of birth cohorts and adolescent marijuana use in the United States, 1976–2007. Addiction. 2011;106(10):1790–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.United States Census Bureau. [Accessed April 15, 2014];Metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas main. https://www.census.gov/population/metro/

- 27.Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, Brogan DJ. Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(5):618–623. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angrist J, Krueger AB. Empirical strategies in labor economics. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D, editors. Handbook of Labor Economics. 3A. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier; 1999. pp. 1277–1366. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mason WA, Fleming CB, Ringle JL, Hanson K, Gross TJ, Haggerty KP. Prevalence of marijuana and other substance use before and after Washington State’s change from legal medical marijuana to legal medical and nonmedical marijuana: cohort comparisons in a sample of adolescents. Subst Abus. 2016;37(2):330–335. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1071723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pacula RL, Kilmer B, Wagenaar AC, Chaloupka FJ, Caulkins JP. Developing public health regulations for marijuana: lessons from alcohol and tobacco. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):1021–1028. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallach P, Hudak J. [Accessed November 20, 2015];Legal marijuana: comparing Washington and Colorado. http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/fixgov/posts/2014/07/08-washington-colorado-legal-marijuana-comparison-wallach-hudak.

- 32.Davis JM, Mendelson B, Berkes JJ, Suleta K, Corsi KF, Booth RE. Public health effects of medical marijuana legalization in Colorado. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(3):373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spoth RL, Randall GK, Trudeau L, Shin C, Redmond C. Substance use outcomes 5½ years past baseline for partnership-based, family-school preventive interventions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96(1–2):57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, Ifill-Williams M. Drug abuse prevention among minority adolescents: posttest and one-year follow-up of a school-based preventive intervention. Prev Sci. 2001;2(1):1–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1010025311161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, Scheier LM, Williams C, Epstein JA. Preventing illicit drug use in adolescents: long-term follow-up data from a randomized control trial of a school population. Addict Behav. 2000;25(5):769–774. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stice E, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Gau JM. Brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for high-risk adolescents outperforms two alternative interventions: a randomized efficacy trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(4):595–606. doi: 10.1037/a0012645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis KM, Bavarian N, Snyder FJ, et al. Direct and mediated effects of a social-emotional and character development program on adolescent substance use. Int J Emot Educ. 2012;4(1):56–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rohrbach LA, Sun P, Sussman S. One-year follow-up evaluation of the Project Towards No Drug Abuse (TND) dissemination trial. Prev Med. 2010;51(3–4):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.